On 9 September, the Swedes went to the polls to decide the composition of its Parliament. The weeks since have been very eventful. First, Stefan Löfven’s social democratic government had to step down. Then the Moderates tried to form a new government, but failed. Now Stefan Löfven again has been given the opportunity to form a government to support him for a second consecutive term.

A bit of context: Political parties in Sweden are traditionally organised in two blocks, the Red-Greens and the Alliance for Sweden. The latest government was a coalition of two of the members of the Red-Green block, Prime Minister Stefan Löfven’s Social Democrats and the Greens, supported by the third member, the (Socialist) Left Party.

At the 2018 election, the Alliance for Sweden with the conservative Moderate Party, the (Agrarian) Centre Party, the Liberals and the Christian Democrats were aiming to form the next government. The “outlier” right-wing nationalist Sweden Democrats were trying to get enough votes to disrupt the traditional binary party system and force other parties to no longer ignore them.

The slow decline of socialism

The elections were expected to follow a similar trend to the ones experienced in other Scandinavian countries and the rest of Europe where we have witnessed the emergence of right-wing populism and the decline of social democratic parties. The latter have been historically very strong in Scandinavia but seem to be struggling to overcome the challenges posed by the changing political climate. In Norway for example, the social democratic Labour Party had been the major political party since the Second World War, often forming single party governments. In the 2017 election they received only 28% of the votes, allowing the Conservatives, for the first time since the war, to sit two consecutive terms[1].

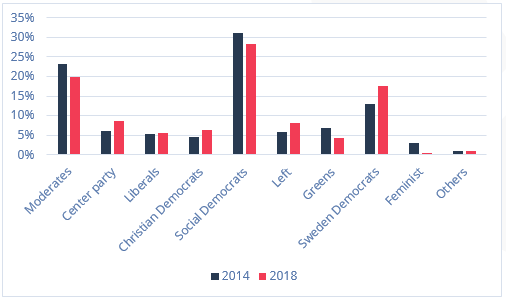

Over the same period, the Swedish Social Democrats also made up the majority of governments since the war, dropping below 40% of the votes only in the 90s. This year, however, they ended up with a historically low 28% of the votes. However, the results were surprisingly better than what the party had feared.

Election results, 2018 election

Source: https://data.val.se/val/val2018/slutresultat/R/rike/index.html

The (moderate) rise of nationalism

The latest results were as much about the downfall of the most popular party as they were about the rise of another. Mirroring European trends, the right-wing Sweden Democrats entered “Riksdagen” (The Swedish Parliament) in the 2010 elections, receiving 5.7% of the votes. This share more than doubled in 2014, rising to more than 12%. This time, they were expected to expand massively, with polls predicting a result between 20 to 30%, which would have made them one of the two largest parties in Sweden. However, the party fell well short of the optimistic prognoses receiving “only” 17,5% of the votes and did not manage to overtake the Social Democrats or the Moderates.

Still, the Sweden Democrats’ share of the vote increased. They share similar views with other European populist parties such as their strong position against immigration. Throughout their 2018 campaign, the party worked to leverage the widening inequality gap[2], and the creation of “ghettos” in certain Swedish suburbs[3]. In the weeks before the elections, several cars were lit on fire by masked youths, leading to higher expectations for Sweden Democrats’ election results. Still, in spite of this supposed ‘perfect storm’, the party “only” secured 62 out of 349 seats in Riksdagen.

What happens now?

While the election results clearly showed the traditional parties in decline, with the right-wing populists increasing their share at the voting polls, the actual outcome of the election is more difficult to determine since no clear winner emerged. Though Stefan Löfven’s Red-Green government had to step down initially, the two main blocks (Red/Green and the Alliance) are practically tied in this election, meaning none of the blocks have the necessary majority to form a new government without including the Sweden Democrats.

Following the elections, the parties appointed Andreas Norlén from the Moderates as the Riksdagens talman (Speaker of the Parliament). Norlén, who is known to be quite conservative, then gave the task of forming a new government to fellow party colleague Ulf Kristersson. Having no other options, Kristersson tried to form a government with the Alliance and the Sweden Democrats, but failed as he struggled to convince the Centre Party and the Liberals. This has opened the doors for an incredible comeback, as Stefan Löfven is now tasked with finding partners to join him in his next government. Löfven will most likely break the block party system, by proposing an alliance with the Liberals and Centre party.

Should Löfven not succeed in forming a government, the task could go back to Kristersson. If neither can create a government, there will possibly be a re-election in Sweden for the first time since 1958.

What do the elections mean for Europe?

At this point, there is no clear answer as to what these results mean for Europe. While Sweden is not amongst the biggest Member States of the European Union, its voice carries a lot of weight in certain debates, notably on climate and the environment.

This election is part of the seismic forces shaking the European political climate, which has seen right-wing populists become increasingly relevant.

Should the Social Democrats and the members of the Alliance decide to cooperate, it would leave the Sweden Democrats’ anti-EU influence to a relative minimum as the government would most likely be controlled by pro-EU parties. However, should the Moderates, or the Alliance, decide to work with the Sweden Democrats, several ministries could end up in the hands of euro-sceptics. The Sweden Democrats are likely to try to secure posts where they can control immigration policy, with the goal of becoming a more restrictive country.

On environment, we should expect to see Sweden more or less carry on the way they have. Both blocks have parties in favour of a strong environmental policy, the Greens and the Centre Party, one of which is likely to be a part of a future government formation.

We will be keeping an eye the process in the coming months, stay tuned.

[1] Not counting Willoch’s government (1981 – 1986) which fell 8 months into its second term

[2]http://www.oecd.org/sweden/sweden-s-economy-is-resilient-and-growing-strongly-but-must-address-rising-challenges.htm

[3] https://www.vg.no/nyheter/utenriks/i/a64aM/derfor-vokser-sverigedemokraterna