Election campaigns changed drastically when political advisors realised voters were no necessarily rational citizens, but consumers driven by impulses, desires, and emotions. As technology grew more influential, vote-gathering techniques became more sophisticated and professionalised. And no example is more compelling of the evolution of this relationship than the one of American politics.

The first major turning point happened with the arrival of television in American homes. Gone were the days of gathering around the fireplace; now families came together around this new entertainment device, which soon became another member of the household. Politicians quickly realised that this small screen was, in fact, a window into the homes of millions of Americans. They understood that the best way to reach people was not through speeches heard on the radio or lengthy texts in the press, but by making them feel as if you were speaking directly to them.

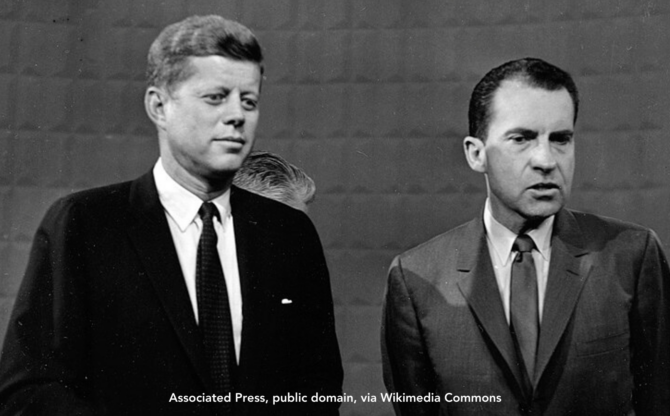

In other words, as Don Draper put it, “It’s not about what you say, it’s about what you make people feel.” This was particularly evident in the debate between Nixon and Kennedy. It was the first debate broadcast publicly and it marked a turning point for the election campaigns. Most viewers declared Kennedy the winner: young, charismatic, and good looking, whereas Nixon, with his experience and seriousness, won over those who listened on the radio.

Since then, image has become the core of any political marketing strategy and an obsession for the all Mad Men, eager to tell stories of success, power, and personal ambition. As a result, political candidates began to be valued not so much for their skills or experience but as commercial products designed to connect with the masses through their image.

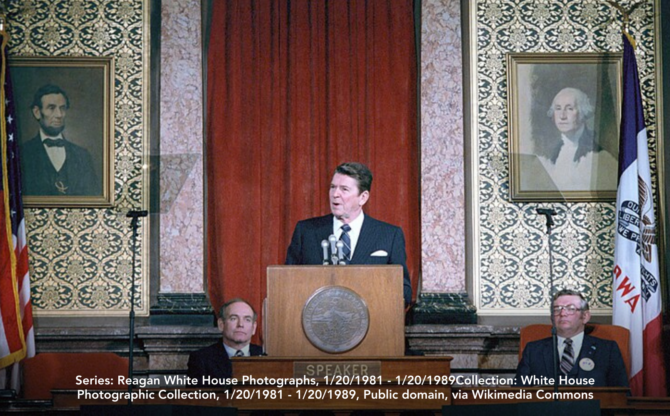

Ronald Reagan, for example, started out as a somewhat average actor, with a strong presence and rhetorical skill. These skills are undoubtedly a key factor in allowing him to reach presidential heights and serve for eight years. In addition to his acting background, which led him to rehearse his speeches for days, Reagan had a technological ally that revolutionised public speaking: the teleprompter. Two screens, nearly invisible for the audience, displayed the text to the speaker, allowing him to maintain eye contact with the public without having to lower his head to read. Thus, the connection with the audience was guaranteed. Today, this device is ubiquitous at all campaign events.

In the 1990s, the internet and personal computers became major forces. Bill Clinton was a pioneer in sending emails to citizens to raise funds for his campaign. Later, George W. Bush and Al Gore used these tools to disseminate messages and create fundraising websites.

This was just the beginning. Shortly afterwards, Barack Obama burst onto the political scene with an innate talent for communication and connecting with the public, understanding like no one else the power of social media to influence the masses and mobilise younger voters.

This ushered in a new era where social media became a crucial battleground for campaigns, not only due to its massive reach but also because of its vast user database. This led to the rise of big data and micro-targeting, allowing for highly personalised messages to specific voter segments. With time, this started to raise concerns about privacy and data protection, especially after the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which revealed how these tools were used to manipulate voters during the Brexit referendum.

This growing intrusive focus on citizens’ private lives has not only enhanced candidates’ images but also created a base of fanatical followers. This dynamic has been exacerbated by the uncontrolled use of bots and artificial intelligence. Trump’s campaign, for example, used data analytics and algorithms to target undecided voters on platforms like Facebook, while social media was flooded with bots spreading pro-Trump messages and misinformation.

This has become normalised and has taken on an even more worrying and dangerous form with the increasing use of deepfakes and augmented reality in election campaigns. These technologies can significantly alter perceptions of reality, posing serious ethical and legal challenges in the political realm.

America may be known for its Frank Underwoods and extravagant political showmanship, but what happens there often affects Europe as well. This is especially true in Brussels, where a wide range of influential figures has not only picked up on the latest marketing trends but has also been hit by deepfakes, misinformation, and other troubling issues. This mix of influences leaves many Europeans with a question hanging: What’s next?